People Who Made Technolgy Great Again

What exercise you recollect of when you hear the word "applied science"? Do you lot recall of jet planes and laboratory equipment and underwater farming? Or exercise yous think of smartphones and machine-learning algorithms?

Venture capitalist Peter Thiel guesses it'southward the latter. When a grave-faced announcer on CNBC says "technology stocks are down today," nosotros all know he means Facebook and Apple, not Boeing and Pfizer. To Thiel, this signals a deeper problem in the American economy, a shrinkage in our conventionalities of what's possible, a pessimism about what is really likely to become better. Our definition of what engineering science is has narrowed, and he thinks that narrowing is no accident. It's a coping mechanism in an age of technological disappointment.

"Technology gets defined as 'that which is irresolute fast,'" he says. "If the other things are not defined equally 'technology,' we filter them out and nosotros don't even look at them."

Thiel isn't dismissing the importance of iPhones and laptops and social networks. He founded PayPal and Palantir, was one of the earliest investors in Facebook, and now sits atop a fortune estimated in the billions. Nosotros spoke in his sleek, flooring-to-ceiling-windowed apartment overlooking Manhattan — a palace built atop the riches of the Information technology revolution. Just it's obvious to him that we're living through an extended technological stagnation. "We were promised flying cars; we got 140 characters," he likes to say.

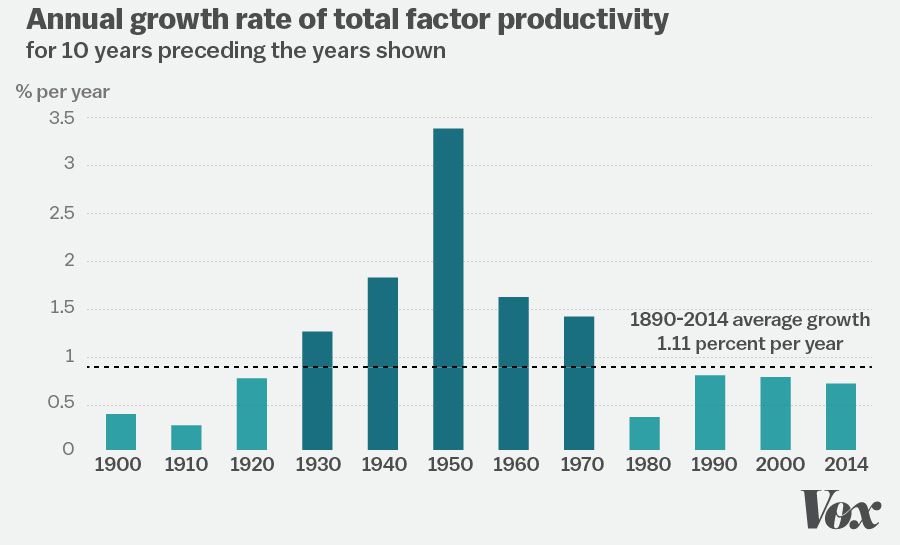

The numbers back him upwardly. The closest the economics profession has to a measure of technological progress is an indicator called full factor productivity, or TFP. Information technology'southward a scrap of an odd concept: Information technology measures the productivity gains left over subsequently accounting for the growth of the workforce and uppercase investments.

When TFP is rising, it ways the same number of people, working with the aforementioned amount of country and machinery, are able to brand more than they were before. It's our best endeavour to measure the difficult-to-define package of innovations and improvements that keep living standards rise. Information technology ways we're figuring out how to, in Steve Jobs's famous formulation, work smarter. If TFP goes flat, then so do living standards.

And TFP has gone flat — or at least flatter — in recent decades. Since 1970, TFP has grown at only nigh a third the rate information technology grew from 1920 to 1970. If that sounds arid and technical, then my error: It means we're poorer, working longer hours, and leaving a worse world for our grandchildren than nosotros otherwise would be. The 2015 Economic Report of the President noted that if productivity growth had continued to roar along at its 1948–1973 pace, the average household's income would be $30,000 higher today.

Robert Gordon, "U.s. Economic Growth is Over: The Short Run Meets the Long Run"

What Thiel can't quite understand is why his fellow founders and venture capitalists can't see what he sees, why they're then damn optimistic and cocky-satisfied amidst an obvious, rolling disaster for human being edification.

Maybe, he muses, it'south simple cocky-involvement at work; the disappointments elsewhere in the economic system accept fabricated Silicon Valley richer, more important, and more valued. With so few other advances competing for press coverage and investment dollars, the money and the prestige menses into the one sector of the economy that is pushing mightily forward. "If you lot're involved in the IT sector, you're like a farmer in the midst of a dearth," Thiel says. "And being a farmer in a dearth may really be a very lucrative affair to be."

Or possibly it'southward mere myopia. Maybe the progress in our phones has distracted u.s.a. from the stagnation in our communities. "Y'all can look around y'all in San Francisco, and the housing looks 50, 60 years old," Thiel continues. "You lot tin expect effectually y'all in New York City and the subways are 100-plus years erstwhile. You tin can look around y'all on an airplane, and it's footling dissimilar from 40 years agone — mayhap it's a bit slower because the airport security is depression-tech and not working terribly well. The screens are everywhere, though. Perchance they're distracting u.s. from our environs rather than making us expect at our surroundings."

But Thiel's peers in Silicon Valley have a different, simpler explanation. To many of them, the numbers are only wrong.

What Larry Summers doesn't sympathize

If there was whatever single inspiration for this article, it was a speech communication Larry Summers gave at the Hamilton Project in February 2015. Summers is known for his confident explanations of economic phenomena, not his la-la-land. Simply that twenty-four hour period, he was befuddled.

"On the 1 hand," he began, "we accept enormous anecdotal bear witness and visual evidence that points to engineering having huge and pervasive effects."

Phone call this the only everybody knows it argument. Everybody knows technological innovation is reshaping the world faster than ever before. The proof is in our pockets, which now contain a tiny device that holds something close to the sum of humanity's knowledge, and it's in our children, who spend all twenty-four hours staring at screens, and it'south in our stock market, where Apple and Google compete for the highest valuation of any company on Globe. How can anyone look at all this and incertitude that we live in an age dominated by technological wonders?

"On the other manus," Summers continued, "the productivity statistics on the last dozen years are dismal. Any fully satisfactory view has to reconcile those two observations, and I have not heard it satisfactorily reconciled."

Many in Silicon Valley have a simple way of reconciling those views. The productivity statistics, they say, are but broken.

"While I am a balderdash on technological progress," tweeted venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, "information technology also seems that much that progress is deflationary in nature, so even rapid tech may not bear witness upwards in GDP or productivity stats."

Hal Varian, the primary economist at Google, is also a skeptic. "The question is whether [productivity] is measuring the incorrect things," he told me.

Bill Gates agrees. During our conversation, he rattled off a few of the ways our lives have been improved in contempo years — digital photos, easier hotel booking, inexpensive GPS, nearly costless advice with friends. "The mode the productivity figures are done isn't very good at capturing those quality of service–type improvements," he said.

At that place's much to exist said for this argument. Measures of productivity are based on the sum total of goods and services the economy produces for sale. But many digital-era products are given away for free, and so never accept an opportunity to show themselves in Gross domestic product statistics.

Accept Google Maps. I take a crap sense of direction, so it's no exaggeration to say Google Maps has changed my life. I would pay hundreds of dollars a yr for the product. In practice, I pay nix. In terms of its direct contribution to Gross domestic product, Google Maps boosts Google's advertising business organisation by feeding my data back to the company and then they tin can target ads more finer, and it probably boosts the amount of money I fork over to Verizon for my information plan. Just that's non worth hundreds of dollars to Google, or to the economy as a whole. The result is that Gross domestic product information might undercount the value of Google Maps in a fashion information technology didn't undercount the value of, say, Garmin GPS devices.

This, Varian argues, is a systemic trouble with the way we measure Gross domestic product: It'southward good at catching value to businesses just bad at communicable value to individuals. "When GPS technology was adopted by trucking and logistics companies, productivity in that sector basically doubled," he says. "[Then] the price goes down to basically zilch with Google Maps. It's adopted by households. So it'south reasonable to believe household productivity has gone upwardly. Simply that'due south non really measured in our productivity statistics."

The gap between what I pay for Google Maps and the value I get from information technology is chosen "consumer surplus," and it's Silicon Valley'south best defense against the grim story told by the productivity statistics. The argument is that nosotros've broken our country's productivity statistics because so many of our bully new technologies are free or near free to the consumer. When Henry Ford began pumping out cars, people bought his cars, and and then their value showed up in Gross domestic product. Depending on the twenty-four hour period you check, the stock market routinely certifies Google — excuse me, Alphabet — as the world's most valuable company, but few of united states of america e'er cut Larry Page or Sergei Brin a check.

This is what Andreessen means when he says Silicon Valley's innovations are "deflationary in nature": Things like Google Maps are pushing prices down rather than pushing them up, and that'due south confounding our measurements.

The other problem the productivity skeptics bring up are and then-called "step changes" — new goods that represent such a massive change in human welfare that trying to account for them by measuring prices and inflation seems borderline ridiculous. The economist Diane Coyle puts this well. In 1836, she notes, Nathan Mayer Rothschild died from an abscessed molar. "What might the richest human in the world at the fourth dimension have paid for an antibiotic, if but they had been invented?" Surely more than the actual price of an antibiotic.

Maybe, she suggests, we live in an historic period of pace changes — the products we use are getting and so much better, so much faster, that the normal ways we endeavor to account for technological improvement are breaking downwardly. "It is not plausible that the statistics capture the step changes in quality of life brought about by all of the new technologies," she writes, "any more the price of an antibiotic captures the value of life."

One trouble with the mismeasurement hypothesis: There'south e'er been mismeasurement

"Yeah, productivity numbers exercise miss innovation gains and quality improvements," sighs John Fernald, an economist at the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank who has studied productivity statistics extensively. "But they've e'er been missing that."

This is a challenge to the mismeasurement hypothesis: Nosotros've never measured productivity perfectly. Nosotros've always been confounded by consumer surplus and step changes. To explain the missing productivity of recent decades, you have to show that the trouble is getting worse — to show the consumer surplus is getting bigger and the step changes more than profound. You have to prove that Facebook offers more consumer surplus than cars once did; that measures of inflation tracked the change from outhouses to toilets amend than the modify from telephones to smartphones. That turns out to exist a very hard example to make.

Consider Google Maps again. It's true that using the app is free. But the productivity gains information technology enables should show in other parts of the economy. If we are getting places faster and more reliably, that should allow us to make more things, take more meetings, brand more than connections, create more value. That's how it was for cars and trains — their real value to the economy wasn't simply sales of automobiles or tickets or gasoline, simply the way they revolutionized our work and lives.

Or take Coyle'due south point about the step change offered past antibiotics. Is in that location anything in our recent history that fifty-fifty remotely compares to the medical advances of the 20th century? Or the sanitation advances of the belatedly 19th century? If so, it'southward certainly non evident in our longevity data: Life expectancy gains take slowed sharply in the It era. A serious appreciation of step changes suggests that our measures of productivity might have missed more in the 20th century than they have in the 21st.

Another problem with the mismeasurement hypothesis: It doesn't fit the facts

The mismeasurement hypothesis fails more specific tests, too. In January, Republic of chad Syverson, an economist at the University of Chicago'due south Booth School of Business, published a paper that is, in the understated language of economics research, a devastating rebuttal to the thesis.

Syverson reasoned that if productivity gains were being systematically distorted in economies dependent on informational technologies, then productivity would look better in countries whose economies were driven by other sectors. Instead, he institute that the productivity slowdown — which is axiomatic in every avant-garde economic system — is "unrelated to the relative size of data and communication technologies in the country's economy."

Then he moved on to the consumer surplus argument. Possibly the all-time style to value the digital age's advances is by trying to put a price on the time we spend using things like Facebook. Syverson used extremely generous assumptions about the value of our time, and took as a given that we would utilise online services even if we had to pay for them. Even so, he found the consumer surplus only fills a tertiary of the productivity gap. (And that's before you get back and offer the same generous assumptions to fully capture the value of past innovations, which would widen the gap today'due south technologies need to close!)

A March paper from David Byrne, John Fernald, and Marshall Reinsdorf took a dissimilar approach but comes to similar conclusions. "The major 'cost' to consumers of Facebook, Google, and the like is not the broadband admission, the cell phone service, or the telephone or estimator; rather, it is the opportunity cost of time," they ended. "But that time toll ... is alike to the consumer surplus obtained from tv (an former economy invention) or from playing soccer with one's children."

There is real value in playing soccer with ane's children, of form — it's merely not the kind of value economists are looking to measure with productivity statistics.

This is a fundamental point, and one worth abode on: When economists measure productivity gains, they are measuring the kind of technological advances that power economic gains. What that suggests is that even if we were mismeasuring productivity, we would see the effects of productivity-enhancing technological modify in other measures of economic well-existence.

You tin imagine a earth in which wages look flat but workers feel richer because their paychecks are securing them wonders beyond their previous imagination. In that world, people'due south perceptions of their economic situation, the state of the broader economy, and the prospects for their children would exist rosier than the economic data seemed to justify. That is not the globe we live in.

According to the Pew Research Center, the last fourth dimension a majority of Americans rated their own fiscal condition as "practiced or excellent" was 2005. Gallup finds that the last time well-nigh Americans were satisfied with the way things were going in the country was 2004. The last fourth dimension Americans were confident that their children's lives would be better than their own was 2001. Hell, Donald Trump is successfully running atop the slogan "Make America Great Again" — the "again" suggests people many don't feel their lives are getting improve and meliorate.

Why isn't all this engineering science improving the economy? Because it's not changing how we work.

At that place'due south a simple caption for the disconnect betwixt how much it feels like technology has inverse our lives and how absent it is from our economic data: Information technology'due south changing how we play and relax more than than it's changing how we work and produce.

Every bit my colleague Matthew Yglesias has written, "Digital technology has transformed a handful of industries in the media/entertainment infinite that occupy a mindshare that'southward out of proportion to their overall economic importance. The robots aren't taking our jobs; they're taking our leisure."

"Information from the American Time Use Survey," he continues, "suggests that on average Americans spend almost 23 percent of their waking hours watching television, reading, or gaming. With Netflix, HDTV, Kindles, iPads, and all the residual, these are certainly activities that look drastically different in 2015 than they did in 1995 and can easily create the impression that life has been revolutionized by digital technology."

But as Yglesias notes, the entertainment and publishing industries account for far less than 23 percent of the workforce. Retail sales workers and cashiers make upward the single biggest tranche of American workers, and you merely take to enter your nearest Gap to see how little those jobs have changed in recent decades. Nearly a tenth of all workers are in food preparation, and even the well-nigh cursory visit to the kitchen of your local restaurant reveals that technology hasn't done much to transform that industry, either.

This is function of the narrowing of what counts as the technology sector. "If you lot were an airplane pilot or a stewardess in the 1950s," Thiel says, "you felt like you were function of a futuristic manufacture. Most people felt like they were in futuristic industries. Most people had jobs that had non existed xl or 50 years agone."

Today, most of us take jobs that did exist 40 or 50 years agone. We utilize computers in them, to exist certain, and that's a real modify. But it'southward a change that mostly happened in the 1990s and early 2000s, which is why there was a temporary increase in productivity (and wages, and GDP) during that period.

The question going frontward is whether we're in a temporary technological slowdown or a permanent one.

The example for cynicism: The by 200 years were unique in human history

The scariest argument economist Robert Gordon makes is also the most indisputable argument he makes: At that place is no guarantee of continual economic growth. It's the progress of the 20th century, not the relative sluggishness of the past few decades, that should surprise us.

The economic historian Angus Maddison, who died in 2010, estimated that the almanac economical growth rate in the Western world from AD 1 to AD 1820 was 0.06 percent per twelvemonth — a far cry from the two to 3 percent we've grown accustomed to in recent decades.

The superpowered growth of contempo centuries is the result of extraordinary technological progress — progress of a blazon and pace unknown in any other era in human history. The lesson of that progress, Gordon writes in The Rise and Fall of American Growth, is elementary: "Some inventions are more of import than others," and the 20th century happened to collect some actually, really important inventions.

It was in the 19th and particularly 20th centuries that we actually figured out how to employ fossil fuels to power, well, pretty much everything. "A newborn kid in 1820 entered a world that was near medieval," writes Gordon, "a dim world lit by candlelight, in which folk remedies treated wellness problems and in which travel was no faster than that possible by hoof or sheet."

That newborn's great-grandchildren knew a world transformed:

When electricity made information technology possible to create light with the flick of a switch instead of the strike of a match, the process of creating light was inverse forever. When the electric elevator allowed buildings to extend vertically instead of horizontally, the very nature of land use was changed, and urban density was created. When pocket-sized electric machines attached to the floor or held in the hand replaced huge and heavy steam boilers that transmitted ability past leather or rubber belts, the scope for replacing human labor with machines broadened beyond recognition. And then it was with motor vehicles replacing horses equally the principal form of intra-urban transportation; no longer did society have to classify a quarter of its agricultural country to support the feeding of the horses or maintain a sizable labor forcefulness for removing their waste.

And so, of form, there were the medical advances of the age: sanitation, anesthetic, antibiotics, surgery, chemotherapy, antidepressants. Many of the deadliest scourges of the 18th century were mere annoyances by the 20th century. Some, like smallpox, were eliminated altogether. Zilch improves a person's economic productivity quite like remaining alive.

More remarkable was how fast all this happened. "Though not a unmarried household was wired for electricity in 1880, nearly 100 pct of U.Southward. urban homes were wired past 1940, and in the aforementioned time interval the percentage of urban homes with clean running piped h2o and sewer pipes for waste product disposal had reached 94 percentage," Gordon writes. "More 80 per centum of urban homes in 1940 had interior flush toilets, 73 percent had gas for heating and cooking, 58 percent had central heating, and 56 percent had mechanical refrigerators."

Gordon pushes back on the idea that he is a pessimist. He does non dismiss the value of laptop computers and GPS and Facebook and Google and iPhones and Teslas. He's simply saying that the stack of them doesn't amount to electricity plus automobiles plus airplanes plus antibiotics plus indoor plumbing plus skyscrapers plus the Interstate Highway Organization.

But information technology is hard non to experience pessimistic when reading him. Gordon does not just fence that today's innovations fall curt of yesterday's. He also argues, persuasively, that the economic system is facing major headwinds in the coming years that range from an aging workforce to excessive regulations to high inequality. Our innovations will have to overcome all that, too.

The case for optimism

Gordon'southward views aren't universally held, to say the least. When I asked Bill Gates well-nigh The Rising and Autumn of American Growth, he was unsparing. "That volume will be viewed every bit quite ironic," he replied. "Information technology's like the 'peace breaks out' book that was written in 1940. It volition turn out to be that prophetic."

Gates's view is that the past 20 years accept been an explosion of scientific advances. Over the course of our conversation, he marveled over advances in gene editing, machine learning, antibiotic design, driverless cars, material sciences, robotic surgery, artificial intelligence, and more.

Those discoveries are existent, but they take time to turn up in new products, in usable medical treatments, in innovative startups. "We will meet the dramatic furnishings of those things over the adjacent xx years, and I say that with incredible confidence," Gates says.

And while Gordon is correct most the headwinds we face up, in that location are tailwinds, also. We don't appear to be facing the world wars that overwhelmed the 20th century, and we have billions more people who are educated, connected, and working to invent the future than nosotros did 100 years ago. The ease with which a researcher at Stanford and a researcher in Shanghai can collaborate must be worth something.

In truth, I don't have any fashion to adjudicate an argument over the technologies that will reshape the world 20 or 40 years from now. Merely if you're focused on gains over the side by side five, x or even 20 years — and for people who need help shortly, those are the gains that thing — then nosotros've probably got all the technology nosotros demand. What we're missing is everything else.

Will there be a 2nd Information technology boom?

By 1989, computers were fast becoming ubiquitous in businesses and homes. They were dramatically changing how any number of industries — from journalism to banking to retail — operated. Just it was hard to meet the IT revolution when looking at the economic numbers. The legendary growth economist Robert Solow quipped, "Y'all tin encounter the figurer age everywhere just in the productivity statistics."

Information technology didn't stay that way for long: The IT revolution powered a productivity boom from 1995 to 2004.

The lesson hither is simple and profound: Productivity booms frequently lag behind technology. As Chad Syverson has documented, the same thing happened with electricity. Around the plough of the 20th century, electricity changed lives without really changing the economy much. Then, starting in 1915, there was a decade-long acceleration in productivity as economic actors began grafting electricity onto their operations. That smash, nonetheless, quickly tapered off.

But in the case of electrification, in that location was a second productivity boom that arrived sometime later on. This was the boom that emerged as factories, companies and entire industries were rebuilt around the possibilities of electricity — the boom that merely came as complex organizations figured out how electricity could transform their operations. "History shows that productivity growth driven by general purpose technologies tin arrive in multiple waves," writes Syverson.

Chad Syverson, "Will History Repeat Itself? Comments on 'Is the It Revolution Over?'"

Could the aforementioned exist true for IT?

Tyler Cowen, an economist at George Mason University and writer of The Peachy Stagnation, believes then. "I call up the cyberspace is merely showtime, fifty-fifty though that sounds crazy."

Stage one, he argues, was the internet as "an improver." This is Best Buy letting you lodge stereos from a website, or businesses using Facebook ads to target customers. This is big companies eking out some productivity gains past calculation some IT on to their existing businesses.

Phase 2, he says, will be new companies built top to bottom around It — and these companies will employ their superior productivity to destroy their competitors, revolutionize industries, and push the economy forward. Examples abound: Think Amazon hollowing out the retail sector, Uber disrupting the taxi cab industry, or Airbnb taking on hotels. At present imagine that in every sector of the economic system — what happens if Alphabet rolls out driverless cars powered by the reams of data organized in Google Maps, or if telemedicine revolutionizes rural wellness care, or if MOOCs (massive open up online courses) can truly drive down the cost of higher education?

These are the large leaps frontward — and in most cases, we have, or will soon take, the applied science to make them. But that doesn't mean they'll get made.

We have the engineering science. What we need is everything else.

Chris Dixon, a venture capitalist at Andreessen Horowitz, has a useful framework for thinking almost this argument. "In 2005, a bunch of companies pitched me the idea for Uber," he says. "But considering they followed orthodox thinking, they figured they would build the software but let other people manage the cars."

This was the ascendant idea of the add-on phase of the internet: Silicon Valley should make the software, so it should sell it to companies with expertise in all the other parts of the business. And that worked, for a while. Only it could only have It so far.

"The trouble was the following," Dixon continues. "You lot build the software layer of Uber. And then you knock on the door of the taxi visitor. They're a family unit business. They don't know how to evaluate, buy, or implement software. They don't have the upkeep for it. And even if yous tin can brand them a customer, the experience was not very skillful. Eventually Uber and Lyft and companies similar this realized that by controlling the full experience and total production you tin create a much ameliorate terminate-user experience." (Dixon's firm, I should notation, is an investor in Lyft, though to their everlasting regret, they passed on Uber.)

The point here is that really taking reward of IT in a company turns out to be really, really difficult. The problems aren't merely technical; they're personnel issues, workflow problems, organizational problems, regulatory problems.

The just mode to solve those problems (and thus to get the productivity gains from solving them) is to build companies designed to solve those bug. That is, notwithstanding, a harder, slower process than getting consumers to switch from looking at one screen to looking at another, or to movement from renting DVDs to using Netflix.

In this telling, what's belongings back our economic system isn't and then much a famine of technological advances but a difficulty in turning the advances we already accept into companies that can actually use them.

In health care, for instance, in that location's more than enough technology to upend our relationships with doctors — merely a mixture of status quo bias on the office of patients, defoliation on the part of medical providers, regulatory barriers that scare off or impede new entrants, and anti-competitive beliefs on the part of incumbents means most of us don't fifty-fifty have a doctor who stores our medical records in an electronic form that other health providers can easily access and read. And if we can't fifty-fifty get that done, how are we going to motion to telemedicine?

Uber'south groovy innovation wasn't its software so much as its brazenness at exploiting loopholes in taxi regulations then mobilizing satisfied customers to scare off powerful interest groups and angry local politicians. In the near term, productivity increases will come from companies like Uber — companies whose competency isn't so much technology as it is figuring out how to employ existing technologies to resistant industries.

"It turns out the hardest things at companies isn't building the technology simply getting people to apply it properly," Dixon says.

My best estimate is that's the respond to the mystery laid out by Summers. Yes, there'southward new technology all effectually united states, and some of it is pretty important. Only developing the applied science turns out to be a lot easier than getting people — and particularly companies — to use information technology properly.

This story is role of The new new economy, a serial on what the 21st century holds for how we live, travel, and work.

Source: https://www.vox.com/a/new-economy-future/technology-productivity

0 Response to "People Who Made Technolgy Great Again"

Post a Comment